Improvisation Notes

This article appeared in LIBRETTO magazine (ABRSM), June 2012

Tim Richards throws some light on interpreting the suggested-notes boxes given in the improvisation sections of jazz syllabus pieces

All ABRSM jazz exams feature improvisation as an integral part of every piece, which can be an unfamiliar task for those not used to providing creative input of this nature. To help with this process, the improvisation sections feature a selection of notes in a box, implying that the player can choose from these notes for as many bars as necessary, until another box comes along, or the written material reappears.

One of the first things to bear in mind is that the suggested notes or scale are not compulsory, and the examiner will not be marking the candidate on whether s/he uses them or not. As long as the result is coherent and musical, you are free to play any note you like! In the piano exams, the same goes for the left-hand accompaniment given in these sections – as it states on the inside front cover of every grade book: “these are given solely as a starting point, or to indicate the style.”

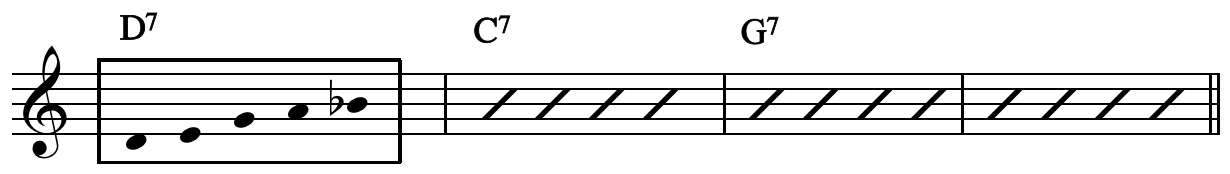

An important aspect of the improvisation boxes is that they often contain scales, arpeggios or pentatonic scales. The teacher should always make sure these are identified, and if possible tie them in with the scale section of the syllabus. On occasions it may not be obvious which scale is being suggested, as it might be incomplete, or start on a note other than the root. Here’s an example from the last 4 bars of the solo section ofBags' Groove (jazz piano grade 1):

Fig 1

Whilst the above scale may at first look like some kind of pentatonic scale on D, closer inspection will reveal that it is in fact a ‘flat 3’ pentatonic on G, as found in the Grade 1 jazz piano scale syllabus. In ‘root’ position this scale has the notes G A Bb D E, but it is given here with the notes in a different order, starting on D.

Why has the scale been disguised in this way? It’s not to deliberately confuse teachers and pupils, but to encourage you to avoid always starting these scales on their root. Because the scale is to be played over three chords (the last 4 bars of a blues in G), not all the notes will sound equally good in every bar. Playing a G on the first beat of the D7 bar can sound like quite a clash if the left hand plays a D7 chord at the same time!

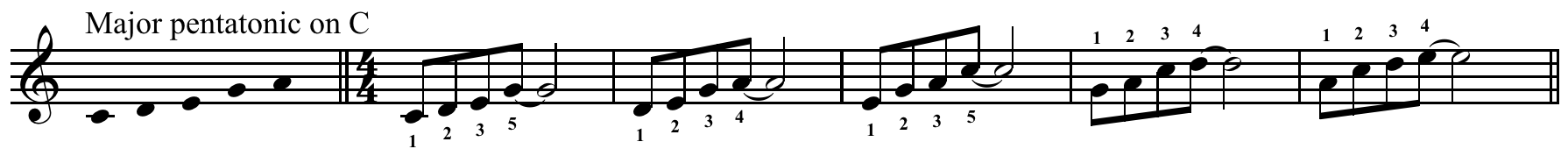

This brings home the desirability of getting to know the pentatonic scales starting on any note, perhaps by practising hand positions such as the following four-note groups:

Fig 2

For younger pupils, or those with smaller hands, similar three-note groups can be played, starting on each note of the scale in turn. Each hand position provides a viable choice of notes for building your own phrases. Being fluent with all five positions allows you to choose a different group of notes each time you perform the improvisation, thereby giving your solos more spontaneity.

The concept of starting a scale on a note other than the root is akin to generating modes of the major scale by going up the white notes on the keyboard, eg: the Dorian scale on D is like a C major scale starting on D, the Mixolydian scale on G is like a C major scale starting on G, and so on...

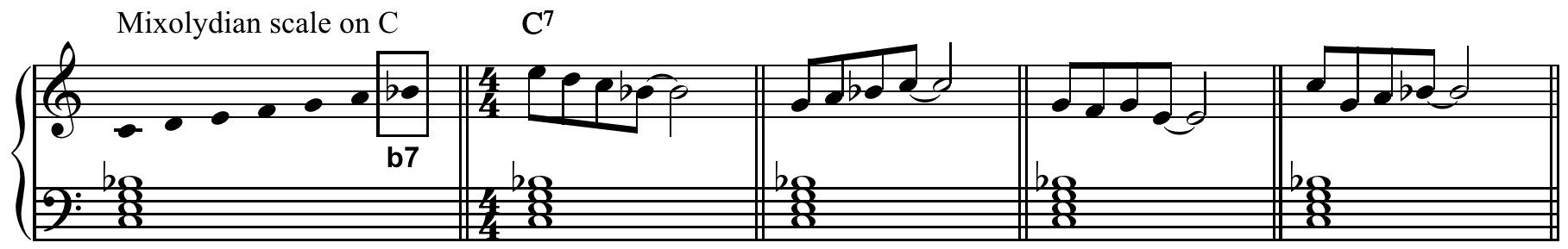

However, it is much more practical to think of the Mixolydian on G (for example) as a scale in its own right, instead of relating it to C major. The important thing to remember about Mixolydian scales is that they fit dominant seventh chords and can be formed by flattening the 7th note of the major scale on the same root. Here’s an example showing the Mixolydian scale on C, with four simple phrases generated from it, following the same rhythmic template as the previous example:

Fig 3

Note how none of the examples start on C. In fact, the notes they finish on are more important than where they start – from left to right the last notes are Bb (7th of the chord), C (root), E (3rd), Bb (7th again) – all notes of the chord itself, as defined by the chord symbol.

Although we’re using a scale to generate our phrases, it’s not necessary to always play consecutive notes. The last thing you need is for your improvisation to sound like a scale exercise! Here’s a few other general points which may be useful to implement with your pupils:

• Play the notes in any register. An octave higher will often sound even better.

• Start on any note (not necessarily the first one given), and play the notes in any order.

• Go outside the box!

• Omit some of the notes. Even if a whole scale is given, you don’t have to use all of it.

• Don’t be afraid to repeat notes. Simple ideas are often good ones.

• Try playing the same group of notes with different rhythms.

• Don’t always start on the first beat of the bar. Try starting on “one and” or “two”.

• In a swing piece try to play some swing quavers. A few triplets will sound good too.

• Try singing the notes in the box before playing.

Singing is important, no matter how good or bad your voice is. If you’re not hearing phrases in your head, then even if you follow the notes in the box it can sound like you’re just moving your fingers randomly. Singing the notes with your pupils is an important step to them creating phrases built on those notes. This is particularly true with pentatonic scales – because they only have five notes they have a distinctive sound which is easy to remember.

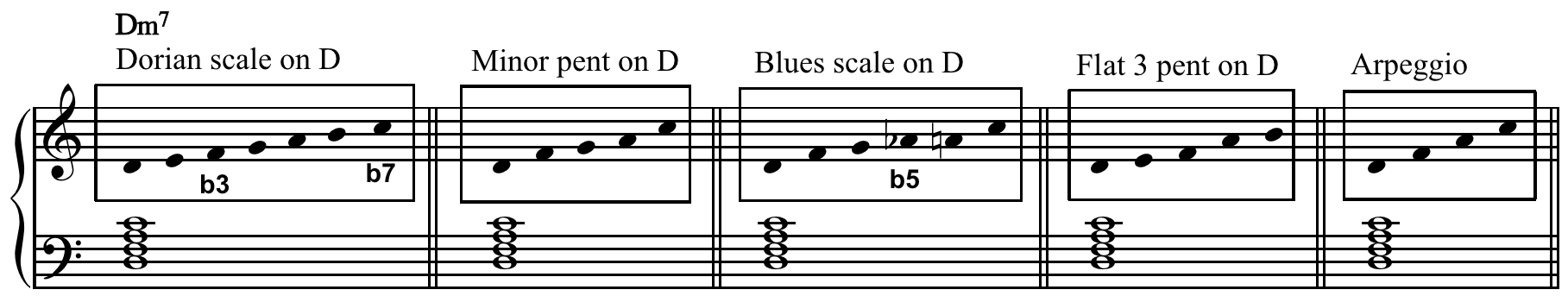

Finally, as the teacher, use your knowledge to point out alternatives, particularly if the suggested notes don’t seem to be working. For a minor seventh chord, for instance, any of the following could be possible:

Fig 4

Try each of these suggestions over the left hand from Eddie Harvey’s popular piece Blue Autumn from the Grade 1 jazz piano syllabus.

The last example, featuring an arpeggio, reminds me of a basic tenet of jazz improvisation that is often overlooked in the face of the scale-based methods given in so many books, ie:

• The most foolproof way to improvise over a chord sequence is to play the notes of each chord as it comes by.

And always be aware of the chord symbols!

Tim Richards is a jazz pianist, composer, ABRSM examiner and author of several books on jazz, blues and Latin piano.

You can read about Tim’s jazz and blues piano books at schott-music.com